By: Alan P. Schwartz

Should Industry be Accepting?

![]() HACCP, what are you talking about? Why would the FDA want to use it for inspecting medical device manufacturers?

HACCP, what are you talking about? Why would the FDA want to use it for inspecting medical device manufacturers?

But why is the FDA now looking to implement a policy that was strictly used for the food industry, for the medical industry? If I am correct, I don’t think these industries have anything in common? I can assure you that if you ever got a chance to attend a Seafood HACCP course, you would learn that they have nothing in common. But, as you will see, the use of the HACCP approach could easily be applied to manufacturing medical devices.

Before delving into the reasons behind the FDA evaluating this inspectional approach, having an understanding of HACCP would be appropriate.

When used properly, the HACCP approach evaluates your medical products and the production process. It also provides assurance that you have determined the hazards associated with the device and its processes as well as the critical control points, and that you are able to control them in some manner. HACCP is a preventive, not a reactive, management tool. HACCP is not a zero-risk system but is designed to minimize the risk of potential hazards.

There are seven principles of HACCP:

1. Conduct a hazard analysis and identify preventive measures. (Prepare a list of steps in the process where significant hazards occur and describe the preventive measures).

2. Identify critical control points (CCP) in the process.

3. Establish critical limits for preventive measures associated with each identified CCP.

4. Monitor each CCP. (Establish procedures for using monitoring results to adjust the process and maintain control.)

5. Establish corrective actions to be taken when a critical limit deviation occurs.

6. Establish a record keeping system

7. Establish verification procedures that the HACCP system is working correctly.

The basic use of this approach is to evaluate each step of your manufacturing process, from receiving components until distribution, and determine if that process reduces or eliminates a potential hazard to the finished device related to any one or more of these three areas: biological, chemical, or physical.

The HACCP guide, which was written for the seafood industry but is presently being applied to the medical device industry, includes forms to perform the Hazard Analysis. Once you have determined your CCP, you then use the HACCP Plan form to look at each CCP. For each CCP, you are required to define the Critical Limits for each preventive measure and outline what, how, how often, and who will monitor these limits. You are also required to define your corrective actions in the event that the critical limits are deviated from, how the information will be recorded, and, finally, how the CCP will be verified.

If you think about it, any good medical device manufacturer has already performed this exercise in some form.

The following is an example of how a medical device manufacturer could apply the HACCP approach to review operations and come up with a HACCP plan.

For this example, a manufacturer of low protein, non sterile, latex examination gloves will be used. (Not all the processes will be covered in this example, but it will show how the HACCP approach is supposed to work.)

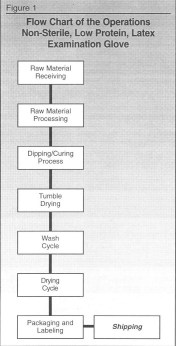

STEP 1. Prepare a detailed flow chart of the operations.

STEP 2. Conduct a Hazard Analysis of the materials and processes. Remember, this exercise should be product and process specific, but you could use the same Hazard Analysis for a family of products that used the same operations for the most part if new hazards are determined not to be present. This Hazard Analysis can be prepared on Form 1.

The hazards that you are trying to determine are to the user, or in some cases, to the practitioner that may apply to the device user. The hazardous areas that should be examined are: biological, chemical and physical hazards for each case.

STEP 3. Once you have determined the CCP, you then define the HACCP Plan using Form 2. This requires that you define the following:

- Significant hazards

- Critical limits for each preventative measure

- Monitoring procedures including:

⚬ What will be monitored

⚬ How it will be monitored

⚬ Frequency of monitoring

⚬ Who will do the monitoring - Corrective actions to be implemented if a deviation from the critical limits are observed

- Records that will be kept

- Verification of the process – how you will assure that the plan is working

STEP 4. Implement the program.

STEP 5. Periodically review the HACCP Plan and make adjustments whenever necessary.

Following is how the process should work for the examination glove process:

STEP 1. Process flowchart, as shown in Figure 1.

STEP 2. Hazard analysis for each step, as shown in Figure 2.

As you see in the first process, which is raw material receiving, we are evaluating all the ingredients as a whole to determine if there are any potential hazards relating to biological, chemical and physical. Raw material is now put in column 1 of the Hazard Analysis Worksheet (Figure 2).

In reviewing each area, you will see that since the gloves are non-sterile, we are not concerned with the biological hazard. This is true throughout the process. If the gloves were sterile, we would be concerned about the biological hazard. This is indicated in column 2.

Regarding the chemical hazard, we are concerned about the potential protein allergic reaction which would be listed under this heading. So, we indicate that there is a potential chemical hazard. But, since there is a washing cycle further on in the process which is used to reduce the protein levels, then at this point in the process, this chemical hazard would not be considered a Critical Control Point. (Remember; CCP are points that would remove or control potential hazard.) In column 2 we indicate that the hazard is a protein-allergic reaction because that is the potential hazard.

The last hazard, physical, which we felt would include pin holes, was not a concern at this point in our evaluation. In column 2, we indicate there is no hazard.

For column 3 of the Worksheet, we indicate whether the potential hazard is significant. For the biological hazard, no, for the chemical hazard, yes, and for the physical hazard, no.

In column 4 of the worksheet, we justified our decision for the biological hazard in that the gloves are non-sterile, for the protein in that a high protein level could cause allergic reactions that could possibly cause death, and for the physical hazards, the ingredients would not cause any physical hazards.

Column 5 of the worksheet requires a certificate of analysis from the vendor for the protein levels of the raw latex. This is to determine how the latex should be processed and the number of wash cycles to be used later in the process.

![]()

In column 6 of the worksheet, again, we indicate that even though the chemical hazard is potentially significant, it is not a CCP at this point in the process because a later process will remove or control this potential hazard.

If there was no wash cycle to reduce the protein levels later in the process, and the protein levels were controlled by the supplier or incoming inspection, then this would be considered a CCP.

We are now finished with evaluating the hazards of receiving raw materials for this process. If your process requires additional evaluations concerning other critical components or materials, then this would be done for each of them.

Now, move to the next step in the flow chart, raw material processing, and go through the process of evaluating the hazards. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

As you can see, there are no hazards found in this process.

The next step is the dipping and curing process. As you can see in Figure 2, there is one potential hazard in the physical area.

(Because it was the last place where the hazard could be eliminated, it becomes a CCP. If the gloves went through a 100% inspection instead of a statistical sample, then this process would not be considered a CCP, but the 100% test would be considered the CCP.)

In this row, in column 5, we state the process is validated to control the dipping speed and the curing time, as well as the curing temperature and the viscosity of the latex solution to assure a good coating on the formers was used to make the gloves.

Later you will see how we will monitor this CCP.

For the next step in the process, tumble drying, there are no potential hazards.

The wash cycle has a CCP because it is used to remove the protein to a safe level. This process is also validated. Again, we test only a sample to assure that this wash cycle worked. If 100% of the gloves were tested for protein, then this step would not be a CCP, but the testing step would be.

As you look down the hazard analysis worksheet, you will see that the next CCP for this process is the packaging and labeling step. This step is indicated as a CCP because of the critical nature of ensuring that the low-protein label was used for gloves treated to reduce the protein levels. If the wrong label was used, someone could be seriously injured.

So, in this process, there were three CCPs. They were the:

• Dipping/curing process.

• Wash cycle.

• Packaging/labeling procedure.

You now fill in the bottom of the worksheet as indicated. It should be signed and dated to be complete.

![]()

STEP 3. The HACCP PLAN, Figure 3.

For each CCP that you have determined in the Analysis, you have to list it in the HACCP Plan.

CCP #1 as indicated in the analysis was the dipping/curing process. Now indicate that in column 1 of the plan. The significance of this hazard is located in column (2), namely pinholes.

The critical limits (column 3) for this CCP are the process parameters that were determined in the validation process, i.e., the speed of the conveyor belt, the temperature of the curing ovens, the viscosity, and the temperature of the latex solution. For this CCP, a visual inspection of the formers would be made for any dirt or breaks that could lead to pin holes, as well as the cleanliness of the latex solution.

What is monitored are temperatures, speed, viscosity, and the cleanliness (column 4). As indicated in Figure 3, how it is monitored (5), the frequency (6) of the monitoring, and who (7) is responsible for the monitoring are all defined.

The corrective action(s) for this step are to adjust the temperature, speed, or viscosity, clean the formers or the change, or skim the latex dipping solution when dirt is observed. If the process is really out-of-specification, a sampling is taken and the batch is set aside to determine if the gloves could be used. This is logged in on the plan in column 8.

The records kept by this company would be the device history records as indicated in column 9.

The verification step is that the Device History Record is reviewed for each batch prior to release, and there is an annual audit to check on the adequacy of the Plan. This is indicated in column 10.

The next CCP(# 2) is the wash cycle, which is used to reduce the protein levels. Again, all columns are filled in and addressed as previously outlined with the dipping/curing process.

This is also filled in for CCP #3, which is the labeling/packaging process.

The completed plan is then filled out on the bottom as indicated and signed and dated as accepted. This is shown in Figure 3.

When one analyzes the HACCP procedure for this type of process; gloves manufacturing, if the operations were already in GMP compliance, it would appear that indicating the CCP in this plant would not change the operations or record-keeping requirements already being set-up by this HACCP Plan. This is what the FDA is expecting to see.

STEP 4. Implement the System.

The most important part of the HACCP Plan is its implementation. You have to ensure that all employees involved in the monitoring are properly trained in how to monitor, how often monitoring must be achieved, and what records must be kept.

You must also provide guidance on who is responsible for taking the corrective actions. Is it the production line person or the Quality Control department personnel?

This needs to be defined.

STEP 5. Periodically review the HACCP Plan to see if it is still viable. Were there any new raw materials that could change or add a CCP? Was there a change in processing or labeling claims that could create new safety hazards?

These must be reviewed and evaluated on a regular basis. On your change form, you could include a space to indicate if a change being made would affect your HACCP Plan. If so, the plan needs to be reviewed and reevaluated.

This system provides the FDA with a clear, detailed map of the critical control points of your operations. It indicates to FDA what the company is doing to assure that these points are being monitored, and what is done in the event of deviation from these points.

Basically, the FDA feels that if a company is using the HACCP approach to conduct a hazard analysis, it demonstrates how they control their CCP. FDA will key in on these points during future inspections. When the FDA investigator feels that the company is controlling these critical areas, the inspection will be over. If done correctly and the FDA sticks to this policy of only reviewing the CCP, the inspectional time at the facilities could be reduced by more than half. This enables the FDA to utilize their staff more efficiently.

Remember, this approach is not a stand-alone system. In order to assure its success, HACCP must be built on a strong GMP program. If violations are found, the FDA will fall back on the GMP regulations to take action. But, the main reason for this approach is that it can be used to focus FDA’s attention on the parts of the process that are most likely to affect product safety. By being allowed to do this, the FDA can forego all the unnecessary learning processes involved with each inspection and key into the plan supplied by the company.

Many questions were brought up by the medical device attendees at a recently held, FDA sponsored HACCP seminar in Indianapolis. Attendees felt FDA had to address these issues in order to get their full support. Some of the more pertinent questions were:

• What would be the difference between a CCP and a Control Point (CP)?

• Will HACCP be accepted by the European Union (EU) now that many of the medical device companies are also ISO certified?

• Will the GMP be put aside during a HACCP inspection and if we take this approach, how can we be sure that it will be followed by the Agency?

• In that HACCP is safety related only, will the FDA also inspect our changes for intended use?

• Will complaints still be reviewed?

• Will the hazard analysis work sheet have to be shown to the FDA?

• Will a CCP disagreement with the Agency result in an FDA 483 point?

• Will this approach be mandatory or voluntary?

• How costly will it be to set up the HACCP plan?

• How many companies are already looking into this plan?

• Does the plan work to assure device safety?

• Who is on the FDA HACCP evaluation team?

• Will there be a written structure to the HACCP inspection i.e., the design control regulations?

• Why should we do this?

Not all these questions could be answered by the FDA representatives present at the meeting. The FDA is currently evaluating this approach by attempting to get volunteers from the industry to try this process. Companies that want to participate in this experiment have to prepare a HACCP Plan and submit it to the FDA. The FDA then conducts an audit of the company to see how the process worked and evaluate whether this plan reduced the inspectional time but still provided the FDA the necessary control to enforce consumer safety Agency. Once the FDA learns more about this process, they will be able to evaluate how difficult it is for companies to implement and the problems associated with conducting these types of inspections. This information enables FDA to determine if they will make a decision as to whether this will be mandatory inspectional strategy or strictly voluntary.

Not all FDAers are leaning towards this approach, though it appears that Dr. Burlington is. As a matter of fact, there is another FDA inspectional approach being brought up from the recent past. It is called the Seven Sub-Systems. This was first brought up in the early 90’s and was supposed to be used for conducting inspections.

These Seven Sub-Systems are:

- Corrective and Preventative Actions

- Design Control

- Production & Process Controls

- Management Controls

- Documents, Records, & Change Controls

- Facilities & Equipment Controls

- Material Controls

Basically, it requires a full FDA inspection to review all these areas. More information on this approach will be forthcoming from the FDA in the near future.

Whether this approach is effective depends on several factors:

- Will the industry see a real benefit to going through this exercise and using it?

- Will the FDA keep their part of the bargain and actually reduce on-site inspectional time?

- Will providing the FDA with a detailed road map of your areas of concern be a potential time bomb?

- Since you are already doing most of this in controlling your operations, what is the real concern of providing the FDA a road map if they will be able to travel it faster and stick to the designated routes?

On the whole, the HACCP approach is one of great value to any company and should be used whether it is provided to the FDA or not. It ensures that a critical evaluation of your operations occurs and determines what areas need upgrading and what will happen in the event of failure. But, can an industry that just went through the traumatic experience of dealing with the new GMP requirements, including design control, now be expected to deal with a new FDA inspectional approach? I am not sure that this is a good time for the FDA to discuss a proposed regulatory approach, especially for the small medical device manufacturer.

As we discussed earlier, but, the FDA is looking for volunteer companies. If you are interested in trying this approach for controlling your operations and working with the FDA to evaluate this plan, they can be contacted through their web site.

About the Author

Alan P. Schwartz is Executive Vice President of mdi Consultants, Inc. He has been providing consulting services to the medical device industry since 1978. Prior to mdi, Alan was an FDA Supervisor of Field Investigations. He has inspected more than 700 companies worldwide and set up over 350 quality programs. mdi has six offices throughout the U.S., and abroad. He can be reached by phone at 516-482-9001 and by fax at 516-482-0186.